I’ll be the first to admit that I’m not a scientist. I’m just a guy who believes in conservation and making California the best it can be. Now that we’re three years into below-average rainfall in California and even the sluggish state government has decided that we’re in a drought, it’s time to look at ways to conserve water. It’s something we should have been doing for years, but … well, we’ve been too busy trying to decide what marriage is while we’re riding on the high speed rail train to bankruptcy.

Just this past weekend the President of the United States came to California to give another in an unending series of speeches that mean – and do – nothing, and then went golfing in the desert. “Blah, blah, blah, you peasants need to share the suffering and stop using water. I’m the President and I say we’re going to support the Renewable Fuel Standard. Now I’m going to go golf at a water guzzling golf course in the middle of a desert.”

The President doesn’t get it. The state government doesn’t get it. We’re in a drought. Why are we being told to suffer, when we’re wasting water and resources so the President can golf?

Why do we continue to support the Renewable Fuel Standard and support ethanol production when it’s proven that the fuel has been discredited long ago as environmentally harmful?

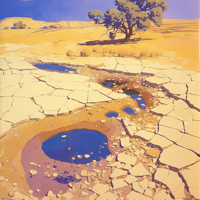

It takes 924 gallons of water to produce a liter of ethanol. One. Liter. Let’s put that in perspective: to fill your 20 gallon gas tank with ethanol requires you to use up 69,854 gallons of water. That’s around 7 tanker trucks full of water.

Tom Tanton wrote an article for the Fresno Bee titled “Making ethanol is wasting California’s water.” From the article:

As conceived in 2005, the RFS was intended to lessen gasoline demand, decrease our reliance on foreign oil and reduce our environmental impact through the introduction of first-generation biofuels like corn-based ethanol followed by a swift transition to truly advanced biofuels. Unfortunately, that transition never occurred, as the industry has yet to commercially produce these fuels. Instead, 80% of the nation’s biofuel blending requirements continue to be met with ethanol — to the detriment of our water supplies, environment and bottom line.

The refining of ethanol across California has come at a steep cost to water supplies. In California, more than 924 gallons of water may be required to produce a single liter of ethanol, according to researchers at UC Berkeley. A biorefinery that produces 100 million gallons of ethanol per year uses the equivalent of the water supply for a town of about 5,000 people — approximately the size of such Central Valley farming communities as Fowler, Gustine and San Joaquin. All in all, it takes 34 times the amount of water to produce one gallon of corn-based ethanol as regular gasoline. Ethanol’s water utilization rate doesn’t seem to fall in line with the idea of a “renewable fuel.” All this water lost and for what gain? The answer is not much for our environment nor for California food producers. The Environmental Protection Agency’s analysis has shown that lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions of corn ethanol were higher than those of gasoline in 2012 and will still be higher in 2017. Moreover, from 2008 to 2011, the mandate has contributed to plowing up more than 23 million acres of wetlands and grasslands — an area the size of Indiana — to grow crops, largely corn. This rapid conversion is driving up greenhouse gas emissions even higher by releasing carbon stored in the soil and by increasing use of fertilizers that swell emissions of nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas.

What’s more: As more and more corn is diverted to ethanol production to meet the RFS, less is available for livestock feed. High demand for corn on account of the RFS has caused extreme price volatility for this key commodity, forcing prices through the roof and at one point increasing prices up by more than 200% from pre-RFS years. Elevated corn costs drove prices for feed — the single largest input cost to food producers — up by 32% in 2012, increasing production costs for food producers across the state. This proved a deal breaker for many of them in the first year of California’s drought, which saw countless farmers forced into foreclosure. Just look at the California dairy industry that has been forced to slash herd sizes and lost hundreds of farms since 2012.

We need to stop using our food and water to make fuel. It’s idiotic.